We are increasingly called upon to hold multiple responsibilities and roles at work. We’re multitasking, or at least trying, even while struggling to cope with our work. But are we actually doing a good job?

A University of Michigan study found that having too many simultaneous tasks can fragment attention and lead to poor performance on each individual task. And yet, multitasking is considered vital to career progress. As founders of The Arts Quotient, we coach business leaders and their teams using methods and practices core to performing arts. In preparing for a live performance, actors train rigorously to remain centred at all times, collaborate with others, and be agile in the moment. These are all skills that are invaluable in the arena of business.

How To Get Better at Multitasking

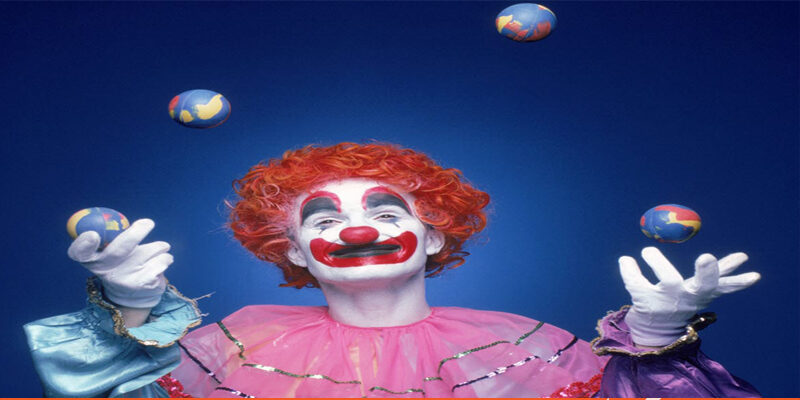

To teach our clients to get better at multitasking, we draw lessons from the ultimate wizards of juggling circus performers to learn the skill of juggling many balls in the air at the same time.

Focus on one ball at a time: Thinking of all of the numerous objects to manage can cause one to panic and fail. Jugglers will tell you that they focus their attention only on the one that needs to be caught most immediately. They literally chunk the complex job of juggling down to micro-steps and make the task manageable. When your to-do list is getting out of control, you will be able to go through it most efficiently by remaining present and committed to one task at a time.

Take time to set the rhythm: The secret to juggling is not the pattern of the objects but the rhythm of the movement. Jugglers will spend a few minutes nailing down a tempo. After that, they don’t think about the act of juggling itself. They simply step into the beat and can then handle more and more objects simultaneously.

Spend a few moments making a plan for yourself with tasks and assigned times for them. Think about what is most suitable for your style. For example, do you prefer to get smaller tasks out of the way first, or perhaps alternate between easy and demanding tasks? Establishing this rhythm can help you flow for the rest of your day, no matter how complex your to-do list.

Block out distractions: A young woman we were coaching said that when her plate is most full, she gets most absorbed in tidying that long-forgotten drawer or watching mindless television. There is a physiological explanation for this. When you are most overwhelmed, anxious, or fearful, our brains literally freeze and can do nothing. While learning to juggle, performers focus not just on the action but also on managing this response in their brain. They recommend facing a wall while practising to avoid distractions. At work, turn off the data on your phone and face it down on your desk, or isolate yourself as you get things done to ensure you are not way-laid by your own sense of panic.

Look ahead and keep the whole pattern in mind: Watch a juggler work and you will see that her eyes are always directed forward or upward, and not looking at the course of any individual ball. Jugglers train to simultaneously do two things to focus completely in the moment on catching the most vulnerable object and not get bogged down by the trajectory of a single ball once it has passed. After all, the job is about keeping the entire routine going. Getting consumed in a sole object can make one lose sight of the broader responsibility. Keep the perspective of the whole picture. Ask yourself questions like, “Which other stakeholders are dependent on you?” or “What other commitments do you have?”

Be patient with yourself through the drops: Learning to juggle is tough and takes time. In the early period, as you hopelessly run behind fast falling balls, you can feel really foolish and the temptation to quit will be high. Yet, it’s a skill that can be mastered by anyone if you repeat it enough times. Novice jugglers talk about the exhilaration of finally being able to keep a few balls in the air, through sheer persistence. Of course, every added ball or task multiplies complexity. In our executive coaching work, we often see great performers shy away from promotions because they are worried about their ability to handle it. But using the same principle of holding faith in self and keeping at the job will eventually make it seem so easy. Amy Cuddy, a social psychologist at Harvard, invites people to keep putting themselves into social situations that seem difficult as a way to master them. Malcolm Gladwell’s work in Outliers suggests that repeated and appropriate practice is key to achieving expertise.

Stay calm and have fun: Juggling is as much a discipline of the mind as of the body. The moment the juggler panics or gets tense, balls begin to drop. Approaching the complex process with ease and a sense of fun is key to success. At work, too, accumulating stress just makes us less productive. Creating sufficient pressure valves for ourselves enables us to keep all our balls in the air with ease.

Barbara Walters once said, “Most of us have trouble juggling.” The woman who says she doesn’t is someone I admire but have never met. So the next time your boss adds one more responsibility to your plate, channel the circus performer in you and take it on with joy.

This article was first published on HBR Ascend.